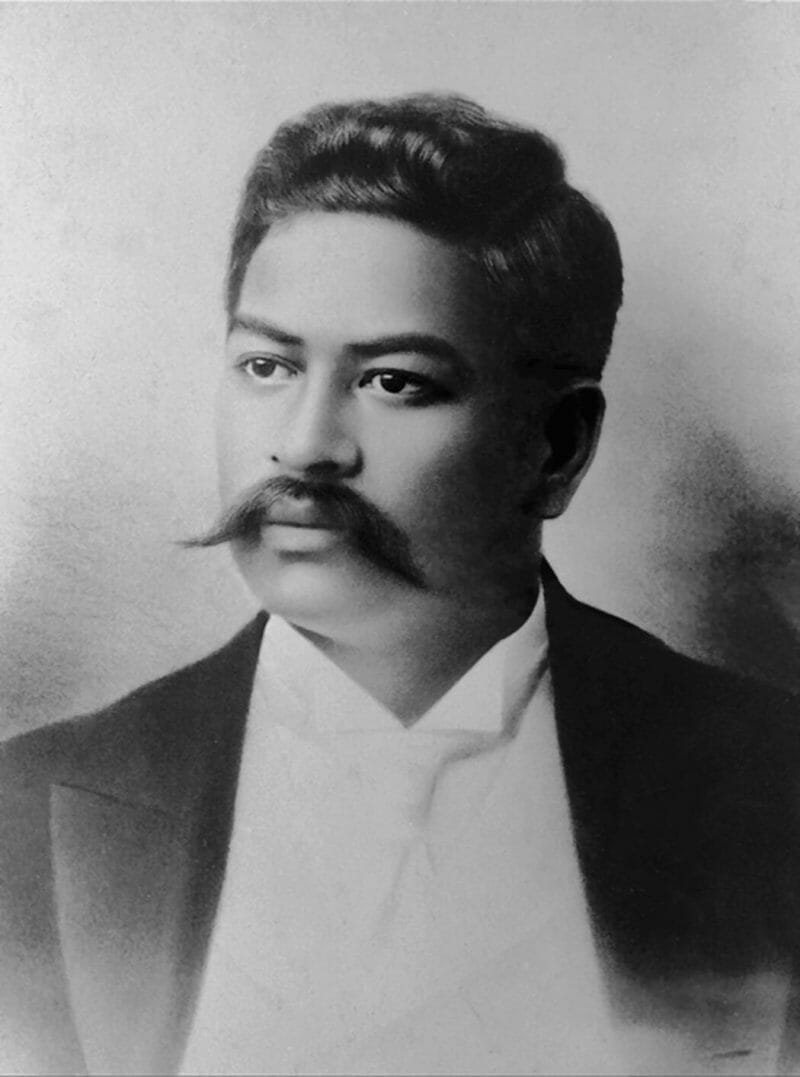

In Hawai’i, March 26 commemorates Prince Kūhiō Day, celebrating the birth of Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole Piʻikoi in 1871 and his life as a royal and revolutionary. Kūhiō championed the Hawaiian people and their lost kingdom after the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, earning him the title Ke Aliʻi Makaʻāinana (“the people’s prince”).

Born in Kōloa, Kauaʻi, Kūhiō was orphaned after the passing of his father, David Kahalepouli Piʻikoi, in 1878, and soon after, his mother, Victoria Kinoiki Kekaulike, in 1884. His maternal aunt remained childless in her marriage, and after Kūhiō’s mother’s passing, she adopted him through the tradition of hānai; Queen Kapiʻolani and King David Kalākaua absorbed the young orphan Kūhiō into the Royal Family of Hawaiʻi.

His uncle, King Kalākaua, encouraged future Hawaiian leaders to attain education abroad, and so Kūhiō studied in the United States and United Kingdom after completing his basic education in the Islands. Kūhiō, alongside his brothers, would go on to be the first to surf in California, introducing the state to the sport in 1885.

In his youth, Kūhiō carried a charming air about him, earning him the nickname “Prince Cupid.” Kūhiō was remarked as charismatic, not unlike his uncle, the Merrie Monarch. After his passing, his successor as Congressional Delegate, Henry Alexander Baldwin, would describe him as such: “Prince Kalanianaʻole was a prince indeed – a prince of good fellows and a man among men; a man of sterling sincerity and strong convictions. He always stood for what he deemed right — yielding to no weakness, and manly always.” (Congressional Record, 1923)

In the years following the Hawaiian Kingdom’s over by the Annexation Club (Committee of Safety) and Honolulu Rifles, Kūhiō was involved in attempts to restore the monarchy, including the Counter-Revolution of 1895. This was the third and final event in the series of Wilcox Rebellions, led by Robert William Wilcox. The Counter-Revolution was a brief war spanning January 6–9, 1896 against the Republic of Hawaiʻi in an effort to restore Queen Liliʻuokalani to the throne. The revolution was unsuccessful, and in the aftermath, Kūhiō, a prince by title no more, was tried for treason and imprisoned for a year.

Upon his release, Kūhiō entered self-inflicted exile. He vowed to never return to a Hawaiʻi that was inhospitable to Hawaiians. He later returned, however, to participate in post-annexation politics, championing the Hawaiian people. For a period, he was a member of the Home Rule Party of Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian Independent Party), which was founded by fellow rebel Robert Wilcox, before it lost Kūhiō’s support, notably after Wilcox endorsed the leper bill which sent Hawaiians suspected of leprosy to Kalaupapa, where they would lose many rights.

Kūhiō would go on to join the Republican party; at the time, he would have found it more welcoming to a progressive person of color, whereas the Democratic ranks were flooded by politicians attempting to block anti-lynching legislation. The Democratic and Republican parties had yet to swap platforms, which occurred between 1860 and 1936. The Republican party favored Kūhiō’s “vogue exoticism” of the time, earning him a seat as Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives from Hawaiʻi Territory for ten terms, until his passing in 1922.

His endeavors in Congress include:

- 1903: Restored the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, a knighthood order inaugurated by Kamehameha V (Lot Kapuāiwa) to defend Hawaiian sovereignty. He served as Aliʻi Moku from the time of its reestablishment to his death.

- 1908: Proposed and obtained funds for the construction of Pearl Harbor. Informed by his experience from his time in the Boer War in South Africa, Kūhio emphasized the importance of establishing a military base to defend Hawaiʻi against, at the time, the looming threat of Japan.

- 1916: Introduced the Hawaiʻi National Park bill, which would cover Kīlauea, Mauna Loa, and Haleakalā. The parks would eventually be split into two, including Hawaiʻi Volcano National Park and Haleakalā National Park.

- 1918: Founded the Hawaiian Civic Club, with the mission to provide scholarships for Hawaiian students, as well as continuing to perpetuate the Hawaiian culture and language. The Hawaiian Civic Club would also push legislation beneficial to Hawaiian people.

- 1919: Presented the initial Hawaiian statehood bill, giving Hawaiʻi more meaningful representation and the power to vote. Statehood would be proposed and declined 48 more times.

- Pre-1920: Supported women’s suffrage, particularly in Hawaiʻi. When all women earned the right to vote in 1920, women in Hawaiʻi were prepared.

- 1920: Introduced the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, a government-endorsed program to house Native Hawaiians. The United States government set aside 200,000 acres for Native Hawaiians, who were deemed “landless and dying.”

On Hawaiʻi Island, Kūhiō is responsible for the Hilo breakwater and wharf, which has provided Hilo Bay with calm waters for harbor activities and shipping for a century, and the inlet hosting the shipping dock is named after him. After Hilo Bay was dredged, along with several others across the islands, he secured funding for a new post office and federal building in Hilo.

Kūhiō passed in his Waikīkī home on January 7, 1922. He is interred in the Royal Mausoleum (Mauna ʻAla) in Nuʻuanu. His passing marked the end of an era, as the last Prince of Hawaiʻi.

2 thoughts on “Celebrate the Legacy of Prince Kūhiō on March 26”

Comments are closed.